“All good things must come to an end.” — Chaucer

Welcome back to Day Seven of the

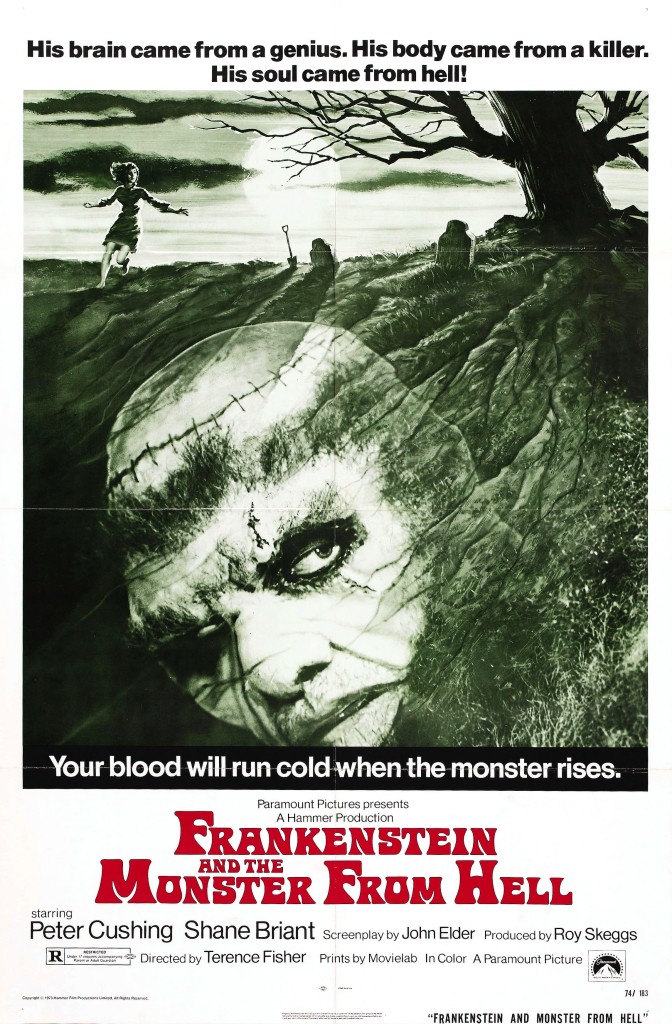

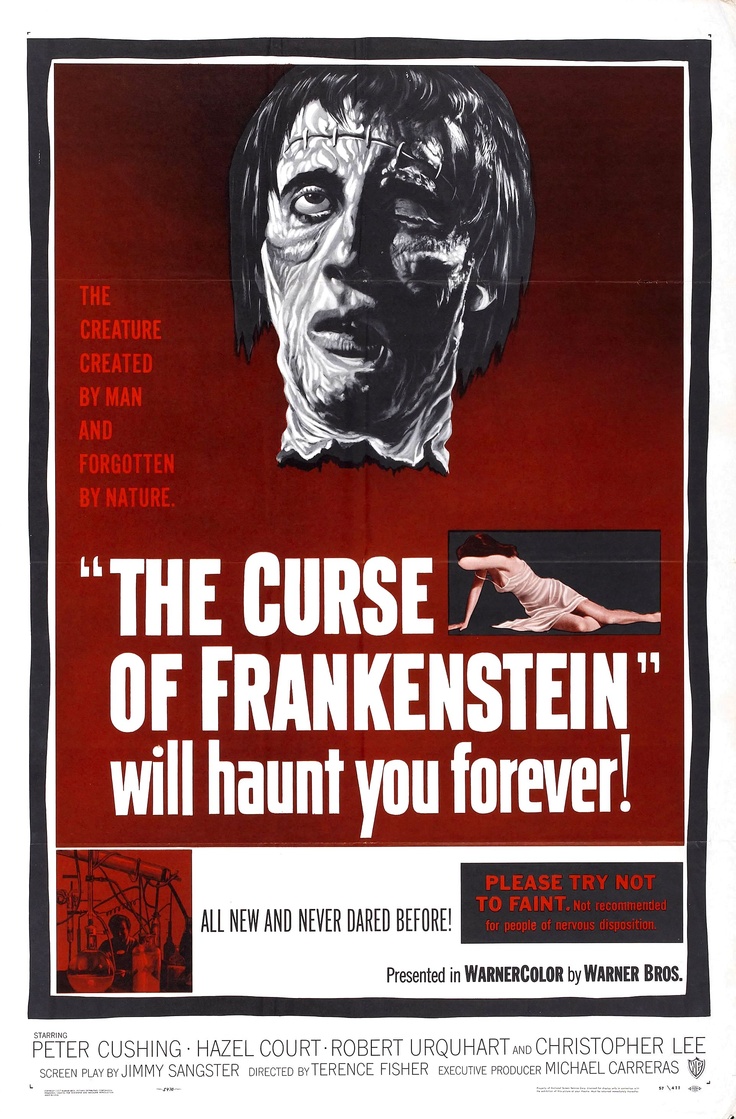

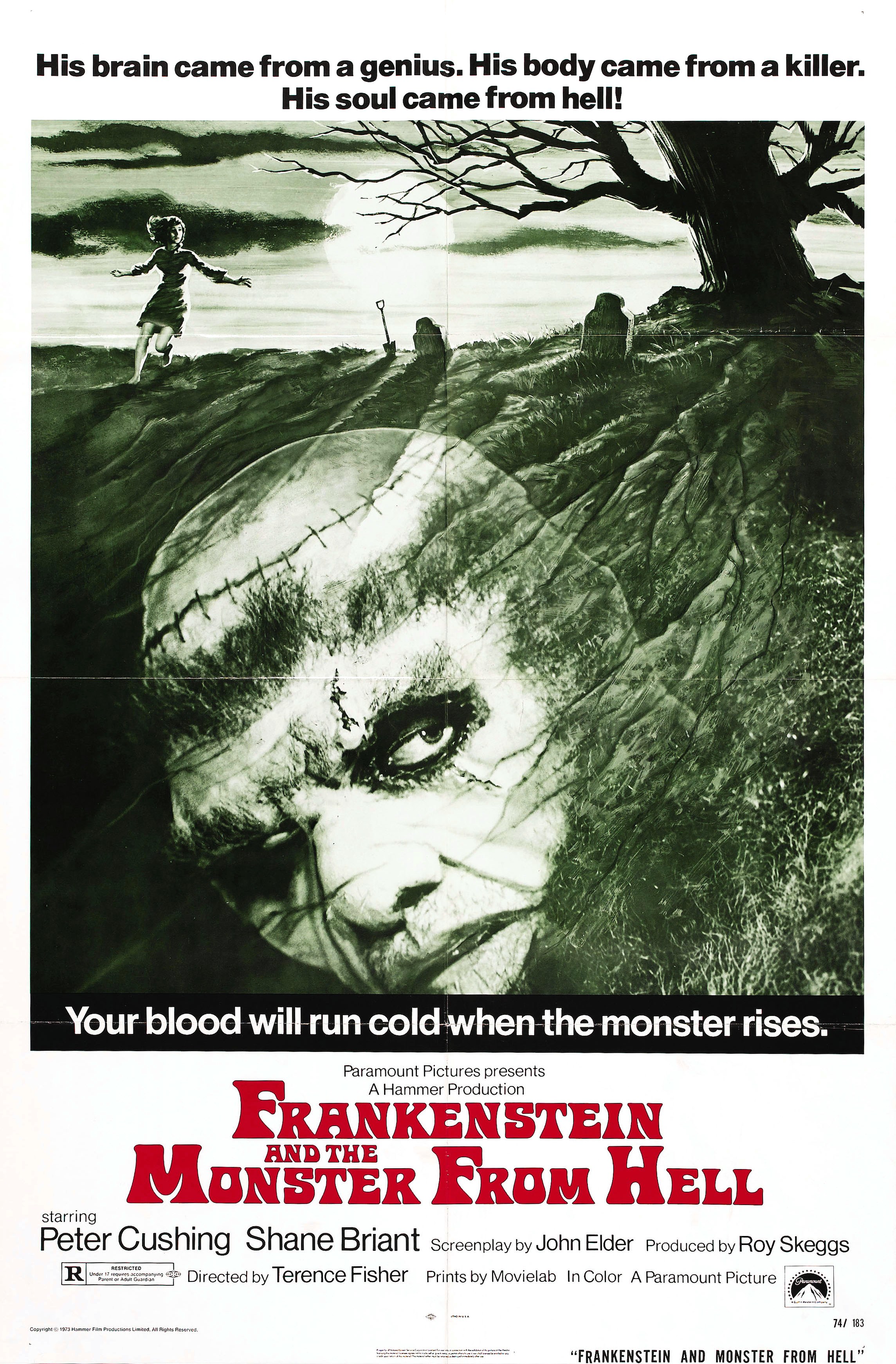

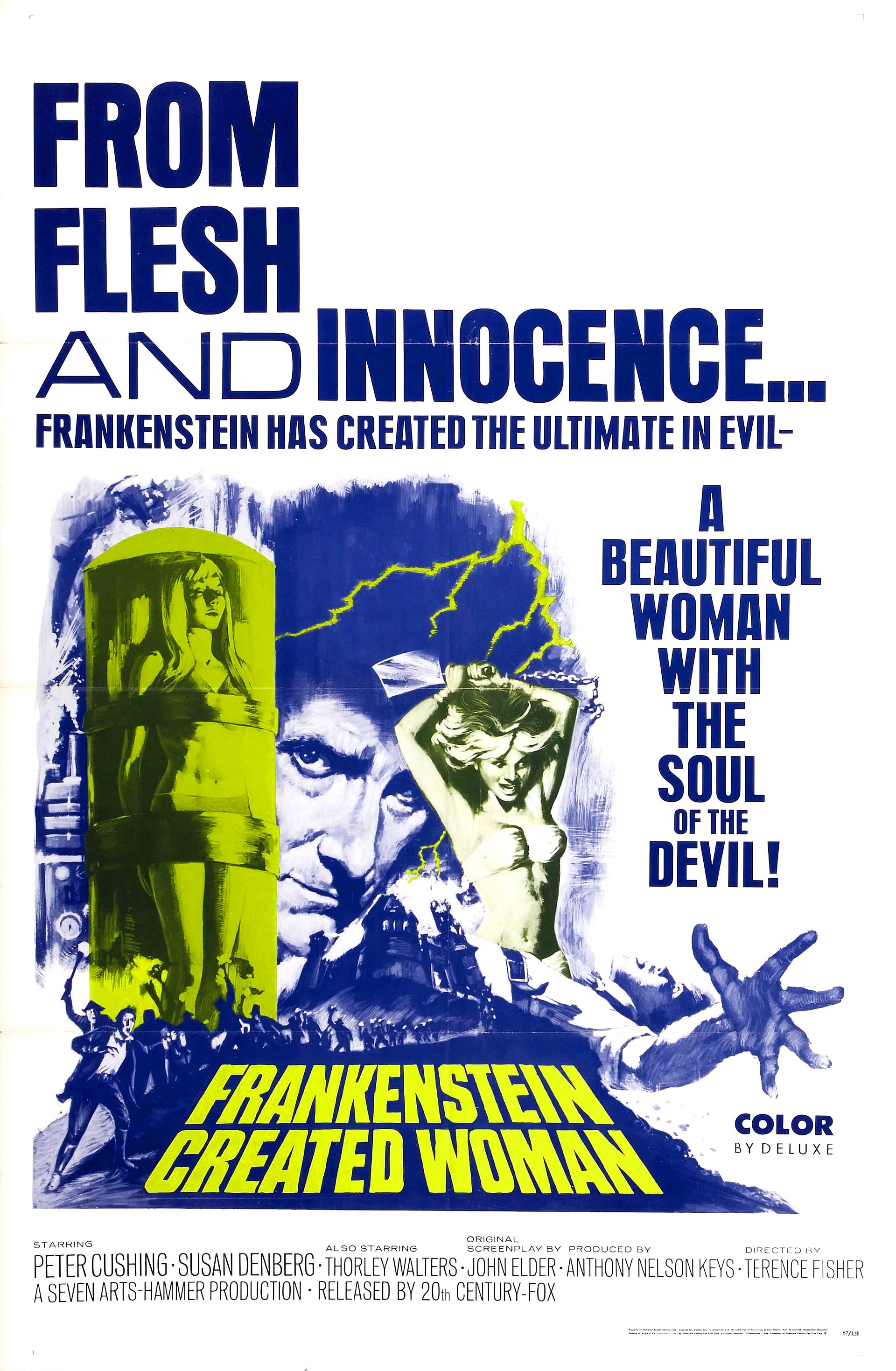

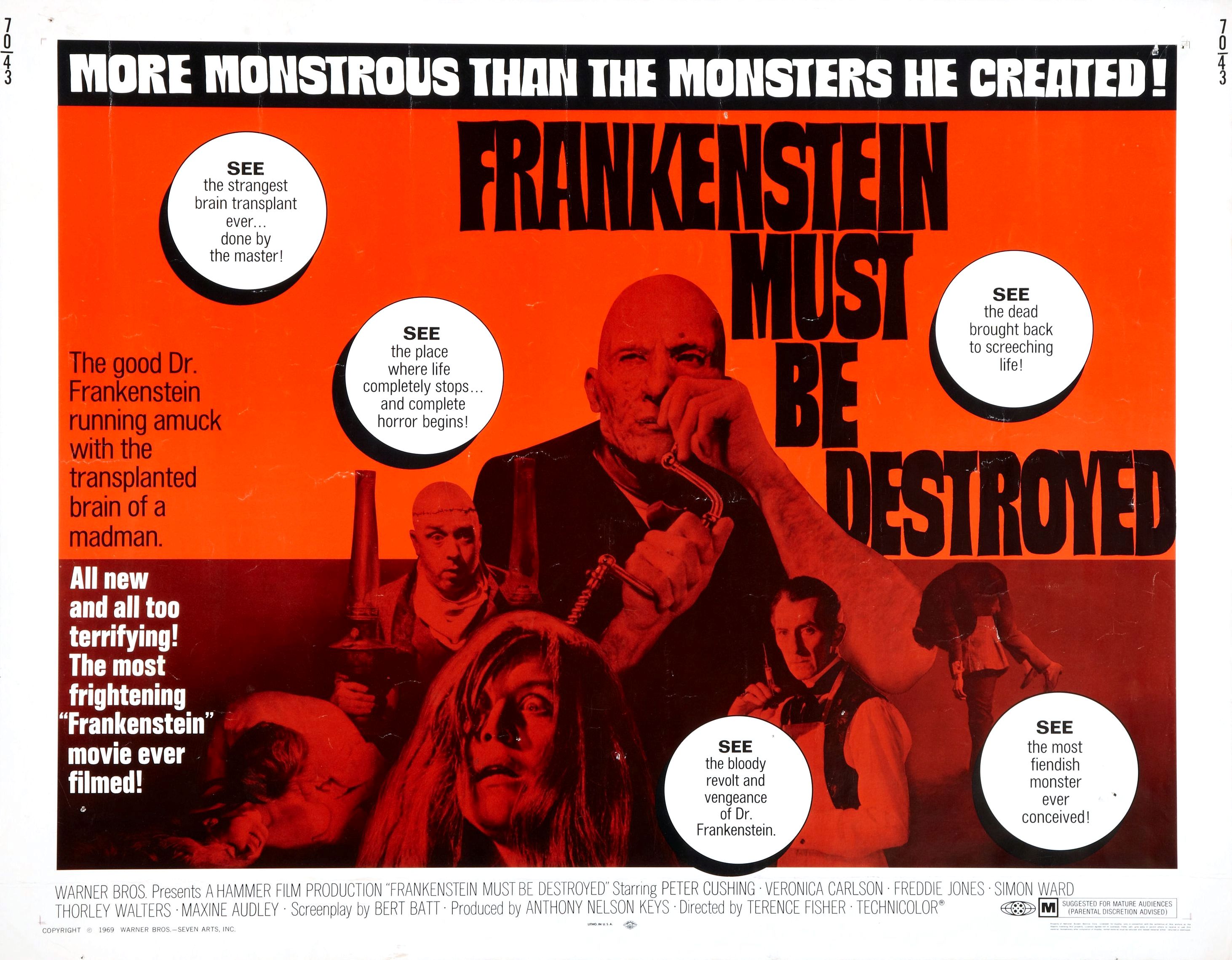

Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon. This is it, the final chapter in the Hammer Frankenstein saga. After Jimmy Sangster’s attempt at a younger, more comedic Frankenstein in The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), we’re back on track with Cushing in the title role and Terence Fisher in the director’s chair (sadly, for the last time). The script, by Anthony Hinds writing as John Elder, brings back familiar gimmicks and themes from the series to bring things to a satisfying conclusion. I must confess that I do not know how obvious the end was for Hammer and company and whether or not they intended to continue the series past Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974).

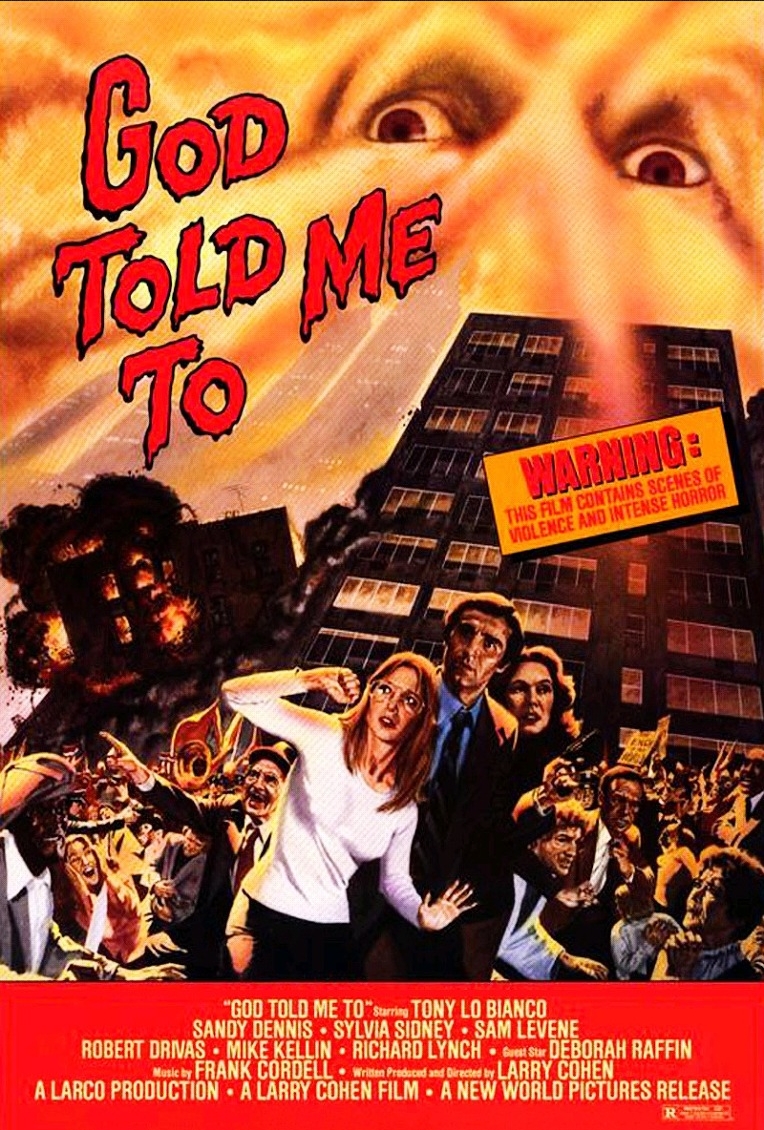

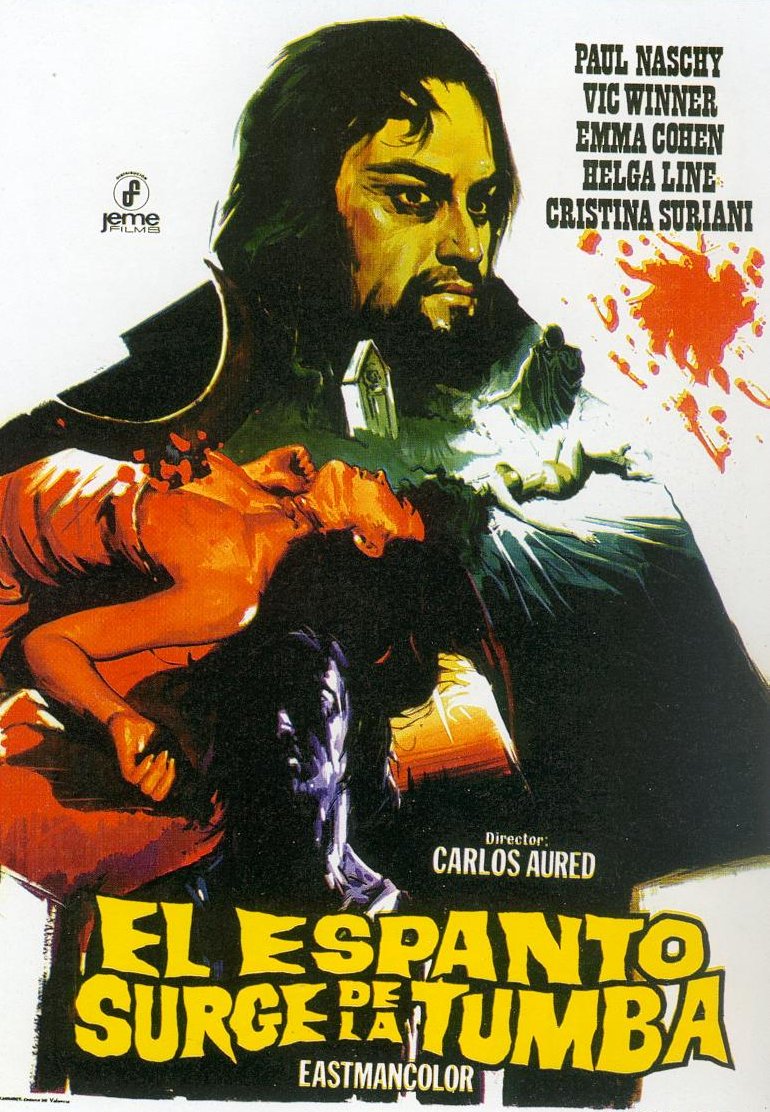

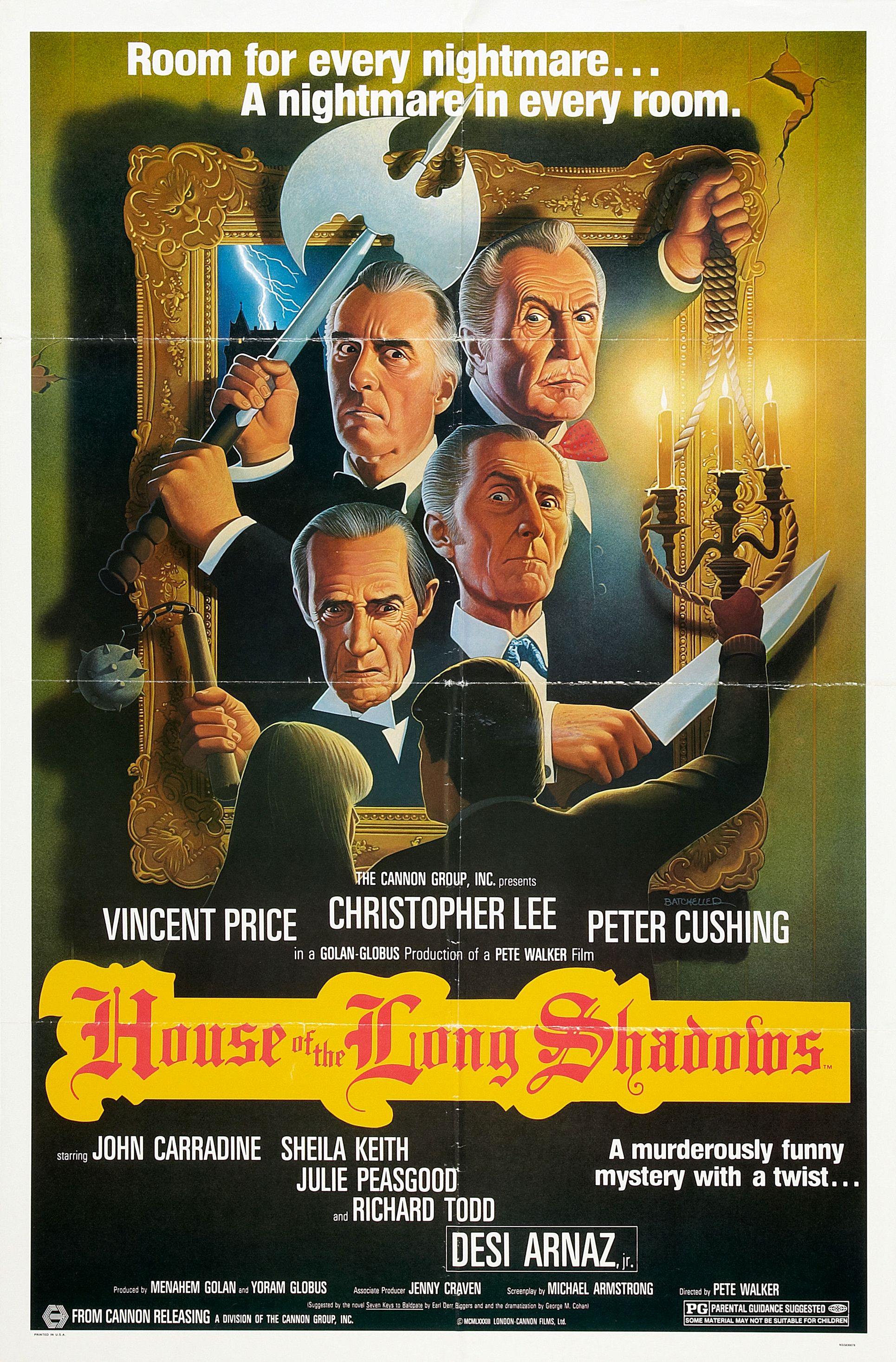

Despite being passed over for Horror, Peter Cushing kept quite busy in the intervening years. After an unbilled cameo as Baron Frankenstein in the Rat Pack farce One More Time (1970), he continued to be a linchpin for Hammer. He appeared in two installments of The Karnstein Trilogy, The Vampire Lovers (1970) and Twins of Evil (1971). He also continued his work in the Amicus portmanteau films with The House That Dripped Blood (1971) (with Christopher Lee, though in different segments), his iconic portrayal of the tragic Arthur Edward Grimsdyke in Tales from the Crypt (1972), as well as Asylum (1972). Lee and Cushing also took their chemistry outside of Hammer with the criminally underrated Horror Express (1972), Nothing But the Night (1973), and The Creeping Flesh (1973). In all, it was a golden age for Mr. Cushing’s fans when his final performance as Frankenstein finally made its way to theaters.

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974)

We begin with a body-snatching, not exactly breaking new ground if you’ll pardon the pun, but the recipient is not Baron Victor Frankenstein as one might assume. No, we are introduced instead to Dr. Simon Helder (Shane Briant), a detached scientist pursuing those familiar forbidden avenues of research first trod by the Baron. He is found out by the authorities and committed to an asylum, much to the shock of Asylum Director Adolf Klauss (John Stratton), who at first assumes Helder must be the new staff doctor.

As the fresh fish on the block, Helder gets some rough treatment, not the least of which is a nasty hose-down as if he were some filthy indigent rather than a learned doctor. When the abuse is interrupted, we zoom in on Helder’s savior and find it to be none other than Baron Victor Frankenstein. In subsequent discussion with Director Klauss, we learn that Victor has taken on a new identity once again as Dr. Carl Victor and that Klauss is a willing accomplice in the charade.

Hammer Films and Director Terence Fisher always gave Cushing great freedom with subtle character notes, including his handling of props. Here, he was given a hand in the design of his wig, but the results show Peter to be a more accomplished actor than wefter and he would later describe the result as making him look like Helen Hayes. Victor also sports his black leather gloves again, his hands burned at the end of either The Evil of Frankenstein or Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, take your pick.

Helder is quite the student of Frankenstein’s work, however, and recognizes him immediately. He convinces Victor to take him under his wing in exchange for assistance in his latest experiments. Helder gets the guided tour and meets some of the other inmates including a man who believes he is God. Victor makes the perhaps self-deprecating joke that the patient is not the first to suffer under that delusion. It should be patently obvious that all of these, from sculptor to mathematician, are mere raw materials for Victor, his living Erector Set. To drive the point home, when the dead sculptor’s coffin is accidentally dropped and falls open, we see he has lost his talented hands post-mortem.

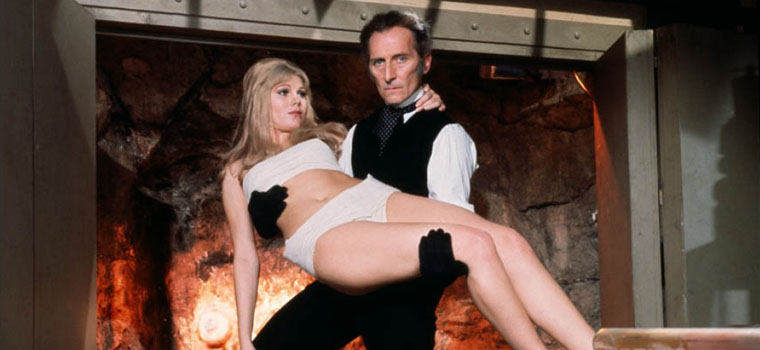

Madeline Smith, Shane Briant, David Prowse, and Peter Cushing in

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974)

The surgery scenes are the most graphic and unflinching depictions of Victor’s work in the series. Briant, having previously appeared in Hammer’s Demons of the Mind (1972), doesn’t even try to hold his own against Cushing, and it perhaps works to the film’s advantage. His Helder proves a valuable assistant, able to perform the delicate operations now denied to Frankenstein due to his damaged hands. Frankenstein is giddy as his project begins to take shape, cackling like a madman in juxtaposition to Helder’s cold callousness, and one could envision them as father and son working on a ’57 Chevy instead of building a man. There’s even a nice little nod to Curse as Victor sits down for some chow before the big brain swap.

Assisting them by handling the stitchwork is the asylum director’s daughter, the mute “Angel” Sarah Klauss, played by the stunning Madeline Smith. Smith had already made quite the impact as a model and actress, appearing in Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970) with Christopher Lee but not Cushing and alongside Cushing (but not as Van Helsing and without Lee) in The Vampire Lovers (1970). With two mad scientists and the Klauss family secrets, it becomes quite clear that the distinction between patient and staff is purely arbitrary.

The patchwork monster is played by David Prowse, who was the only actor to play such in two separate installments of the Hammer Films Frankenstein series. He would, of course, re-team with Cushing as the diabolical duo of Darth Vader and Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977). He also trained Christopher Reeve for Superman (1978) after getting over his own disappointment at not landing the title role.

In his single-minded madness, Victor seems to have forgotten that his supply of brains all suffer from a fatal flaw. While his selection, the Professor, may have been a mathematician and violinist, he was also clearly a madman. When the “Monster from Hell” takes his first steps, we shouldn’t be surprised that a murderous rampage ensues.

Once the creature is overwhelmed and destroyed, Frankenstein is undeterred. Victor has them break out the hose to clean up so that he can start again fresh. This may be his swan song, but in his final moments on film, he reminds us that he’ll never, ever stop.

All good things must come to an end. And so it goes with the Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon, the Hammer Frankenstein films, and sadly, the life of Mr. Cushing, who passed on August 11, 1994. He is fondly remembered by friends and fans alike. His work stands as a testament to his dedication, his talent, and his humility.

Thanks to everyone who participated, moderated, commented, or lurked during the Blogathon. Heartfelt thanks also go out to my patient wife, who has endured my own Frankenstein-like obsession with these films for the past two months. I’m sure she wouldn’t have been shocked to receive a phone call requesting bail money. “My co-workers all laughed at me when I tried to build a man from paper clips and used coffee cups, but I’ll be the one laughing when Office Maximus and I have our revenge!”

Lastly, but surely not least, thanks to the late, great Peter Cushing for providing us all the inspiration to share our collective artistic gifts with each other and the world as he so generously and graciously did. He has my continued appreciation and admiration.

Rest easy, good sir.

So, let’s do it again in 2113. I intend to be here. As evidenced in these six films, brain transplants are easy to facilitate if you have the right training, equipment, and materials. After all, what could go wrong?