It should’ve been obvious, the evil dog that all other evil dogs are compared to, sometimes literally.

Cujo is the tenth novel by celebrated horror author Stephen King (counting three under his Richard Bachman pseudonym). Written during a particularly dark period in his struggle with alcoholism, the novel serves as a treatise of sorts on the links between mental illness and violence and the gray area where culpability lies.

The name “Cujo” comes from the alias “Kahjoe” of Symbionese Liberation Army founding member Willie Wolfe. At the height of their violent revolutionary activities, the press often misspelled the name. The SLA and their leader, Donald DeFreeze, served as nightmare fuel for King, with the latter directly inspiring the creation of his recurring villain Randall Flagg.

The plot of the novel and film adaptation are largely the same, though there are distinct differences in resolution that I will not go into here to avoid ruining either. The basic premise is almost too simple. A mother and her panicked son are stuck in their P.O.S. Ford Pinto while the unrelenting sun threatens to give them heatstroke and a rabid St. Bernard (the eponymous Cujo) lurks outside, waiting to rip their throats out.

Other than the ending, the other major deviation from page to screen lies in the subtext. The film deals primarily with the family drama portion of the plot, with Cujo serving merely as catalyst and antagonist, mindlessly rabid and driven almost exclusively by primal instinct. By having a portion of the novel from Cujo’s own perspective, we see firsthand his slow degeneration into rabid savagery and his desire to do what he knows to be right. Alongside subplots of domestic violence and infidelity, Cujo’s plight is a sympathetic one.

“It was a goddam fragile world, as fragile as one of those Easter eggs that were all pretty colors on the outside but hollow on the inside.” — Stephen King, Cujo

Stephen King teaches a harsh lesson. You’re never truly rid of the childhood monster lurking in your closet. That nameless dread just moves with you, from the bedroom to the boardroom, to your own child’s school, into your marriage bed instead of under it.

Admittedly, I have no earthly idea how such themes could be communicated in film. Dog narration would undoubtedly have made the entire affair laughable outside the hands of an avant-garde director like Nicolas Winding Refn or Lars von Trier. The small town suburban life segments would likely have ended up with a decidedly surreal tone, however. Maybe it’s best they kept things simple for movie audiences.

It is uncertain whether or not original director Peter Medak (The Changeling) would have been able to pull off a film with a tone so unfathomably dark. He was replaced after only a few days of shooting by Lewis Teague (Alligator). Looking at their lists of respective credits, I would have thrown my money after Medak, but hindsight is, as they say, 20/20.

Teague had some definite assistance in the form of impressive cinematography by Jan de Bont (Speed, Twister, and The Haunting). Jan de Bont deconstructed a good half dozen Ford Pintos to get the claustrophobic interior shots used throughout the latter half of the film. Luckily, they didn’t need Jaguars, so they got off cheap.

One of the team’s greatest achievements was the construction of dual sets for Tad’s bedroom, a normal sized set when lit and an elongated set for Tad’s fearful slow-motion sprint to his bed through darkness. An innovative overhead shot with the camera flipping upside-down as he dives/falls into the bed makes the brief scene rather iconic and one of my favorite depictions of irrational childhood phobias. The sequence also parallels nicely with later action when Tad’s mother, Donna, must judge the distance from the besieged car to the perceived safety of a front porch or to a possible weapon.

Cujo (1983)

Our film opens with a frolicking bunny, not exactly the paragon of menace, the Rabbit of Caerbannog notwithstanding. The score by Charles Bernstein does a good job of dancing between happy-go-lucky trilling and more sinister tones. The latter hit a crescendo as our title St. Bernard steps into frame, clearly with malicious intent toward the fuzzy bunny.

The exact number of dogs used for the film is unknown with different cast and crew members citing various numbers, ranging from five to a dozen. Thankfully, none were hurt making the film. Likewise, the nimble rabbit escapes harm.

Cujo, however, is not so lucky within the context of the story. He runs the rabbit into a hole and gets his big muzzle stuck right in. Cujo’s frustrated barks rouse a flock of bats, getting him a bite on the snout for his recklessness. Our inciting incident lies less than four minutes in. That’s wasting no time.

Just as the words “Based on the Novel by Stephen King” hit the screen, we cut to a creepy looking house covered in shadows like ivy. Within this sprawling home live the Trentons, Donna, Vic, and their young son, Tad. This trinity forms the core of Cujo.

While working primarily a television actress in the late 1970s, Dee Wallace (Donna Trenton) was no stranger to horror, having appeared as the married daughter in The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and as the lead protagonist in The Howling (1981). Before Cujo, she would be best known as the mother in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982).

With all due respect to author Stephen King, I do not agree with his assessment that Dee Wallace deserved an Oscar nomination for her performance. Not even close. In his novel, Donna Trenton is a complex woman coming to grips with the realization that time is not on her side, that she very well may have to shelve her personal hopes, dreams, and aspirations to adopt the role of dutiful mother and wife.

The film version of Donna is a helpless, incapable shrew, the kind of career dependent who cannot change a tire or even a light bulb without assistance. Her infidelity seems casual, not a cry for help or relevance, but a selfish indulgence at the expense of her loving family. To see her trapped in that car with a screaming Tad validates every Lifetime Network “woman in jeopardy” cliché rather than being the last stand of a desperate woman.

Daniel Hugh Kelly fares better as Vic Trenton, but perhaps benefits from diminished screen time. Kelly was also a veteran of television, the third actor to play Frank Ryan on the long-running ABC soap Ryan’s Hope. Shortly after the release of Cujo, he would play the McCormick half of Hardcastle and McCormick for three seasons on ABC.

Last, but certainly not least, Cujo introduced 7-year-old Danny Pintauro to audiences. As Tad Trenton, “The Tadder”, Pintauro primarily serves as a plot device for his parents’ conflict. Other than obvious emotional scarring, he isn’t likely to walk away from the terrifying events of the film with any kind of epiphany. He doesn’t have any ambivalence or doubt, he just predictably wants a safe environment and a loving family around him. Pintauro’s professionalism, publicly lauded by many who worked on the film, likely helped him land the role of Jonathan Bower on all 196 episodes of the ABC sitcom Who’s the Boss?

Meeting his parents, it’s easy to see how Tad would grow up to be a panicky, neurotic little boy. There are some early hints of a supernatural threat, but Director Lewis Teague would abandon these notions under the idea that there was no way to keep them from appearing “hokey”. Our first obvious threat to this domestic bliss is the arrival of furniture stripper/tennis patsy/trombone player Steve Kemp (Christopher Stone).

Vic thinks him just an element of local Maine color, but, unbeknownst to him, Steve is cuckolding him something fierce. The ironic bit about this relationship is that Stone was Dee Wallace’s husband in real life at the time, and played her character’s husband in The Howling (1981), where he would be the unfaithful one, albeit under the influence of lycanthropy.

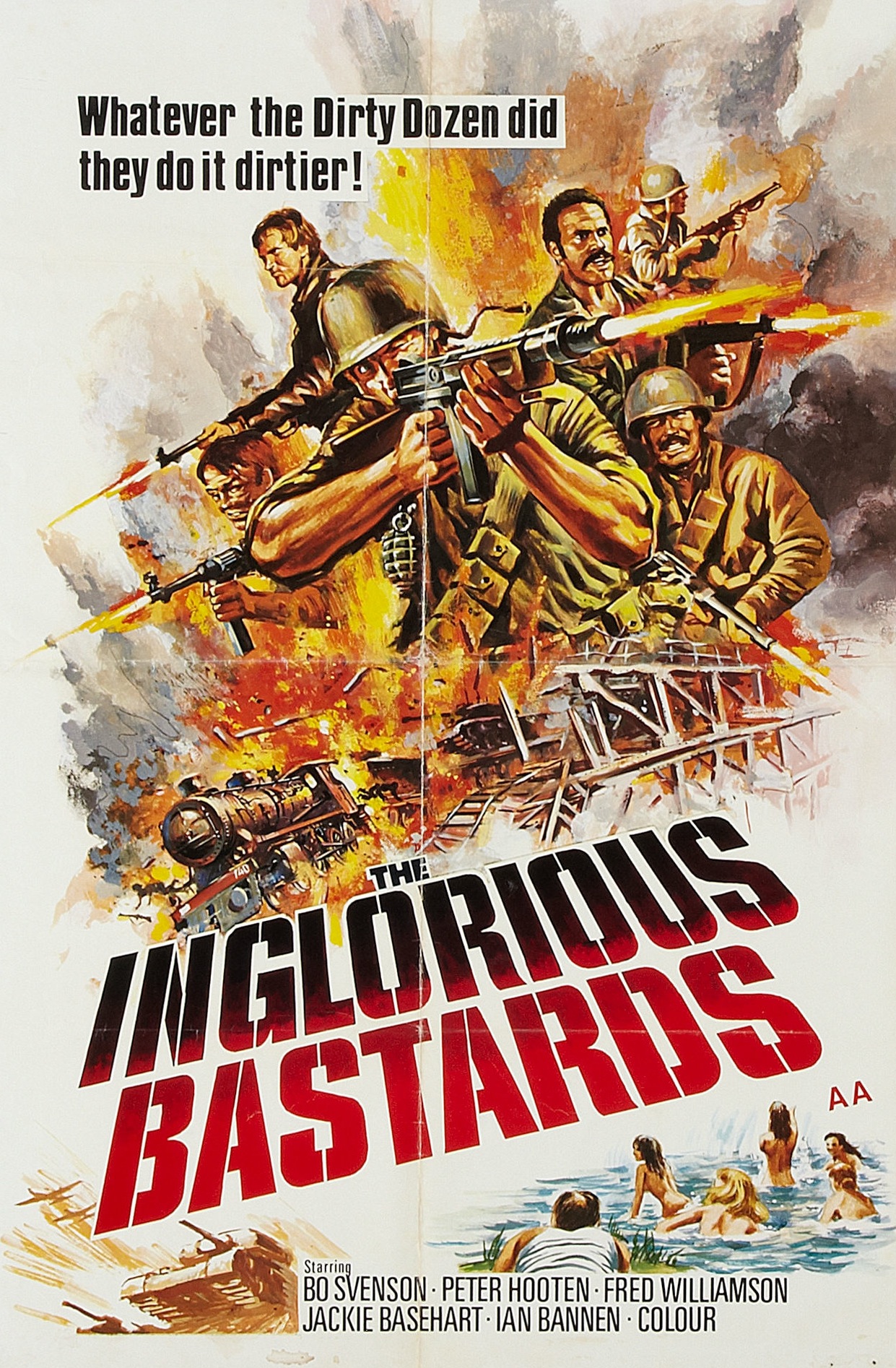

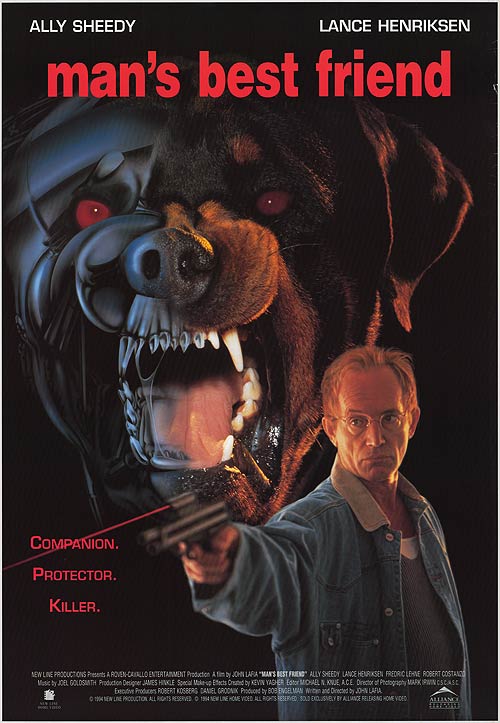

When Vic’s Jaguar convertible starts acting up, he is directed to Joe Camber (Ed Lauter), the local shade tree mechanic. Lauter replaced William Sanderson (Blade Runner) at the same time Teague replaced Medak as director. Sanderson would get his shot at a similar role in Man’s Best Friend (1993), #11 on this list and covered almost exactly one year ago. Given the aggressive and abusive nature of Camber, Lauter was the better pick here. I just don’t see Dee Wallace being intimidated by Larry from Newhart.

It is when retrieving the fixed car that the Trenton family first encounters the Camber family dog, Cujo. There’s actually a clever bit of juxtaposition here as Donna first looks on Charity Camber’s matronly lot in life with a mix of contempt and horror then feels true terror when she sees the massive Cujo padding towards her vulnerable son.

Oblivious to the potential danger posed by the oafish pet, Tad is fascinated by Cujo. Despite musical cues and Donna’s trepidation (as well as that of the viewer), there is no evidence of anything untoward here. Cujo is still on his best behavior and doesn’t even muster up a growl at the visiting strangers.

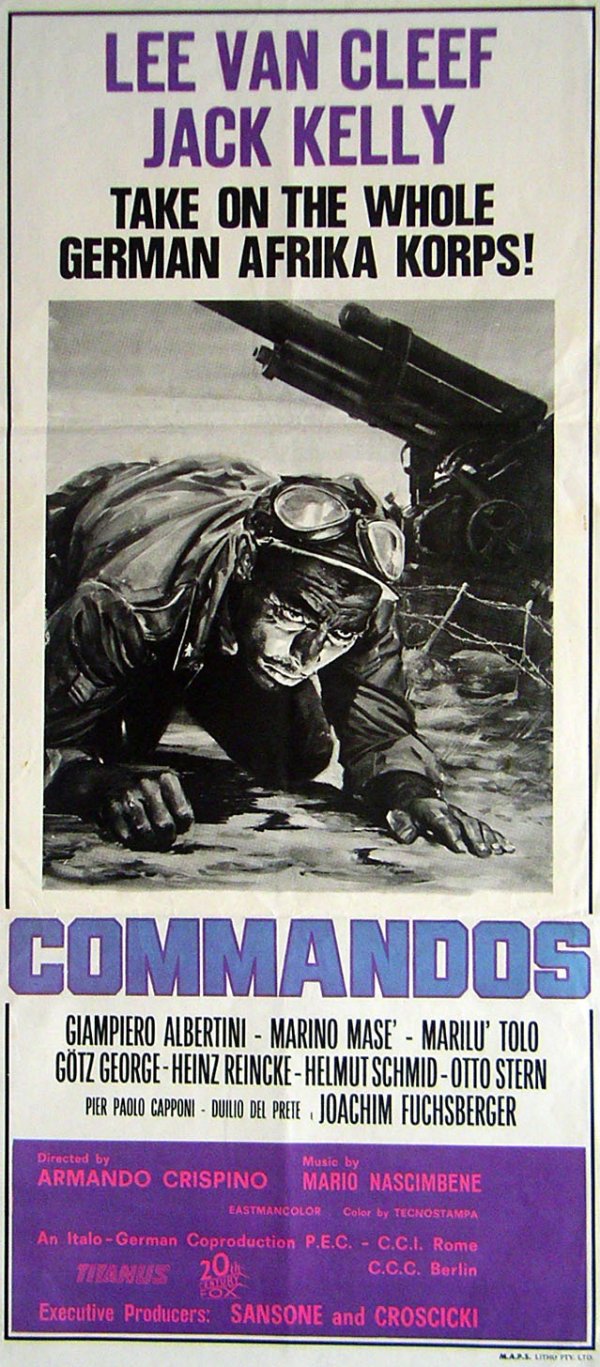

This 1983 TV ad seems determined to keep Cujo’s identity as a rabid dog a secret.

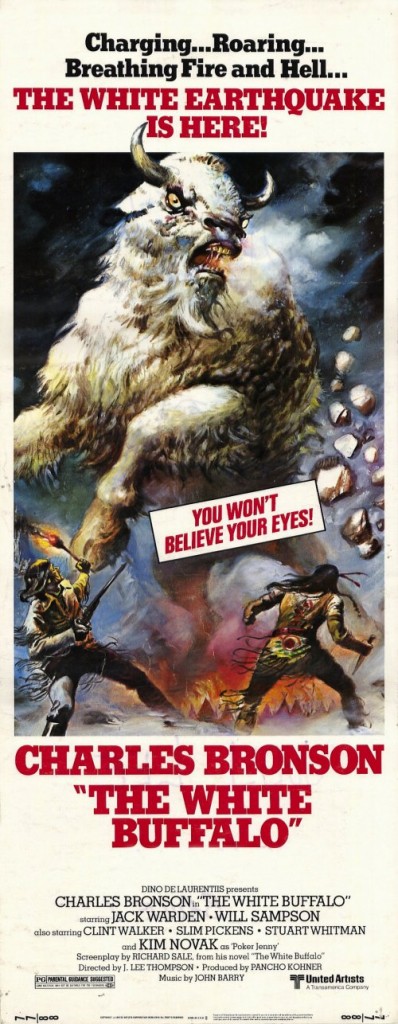

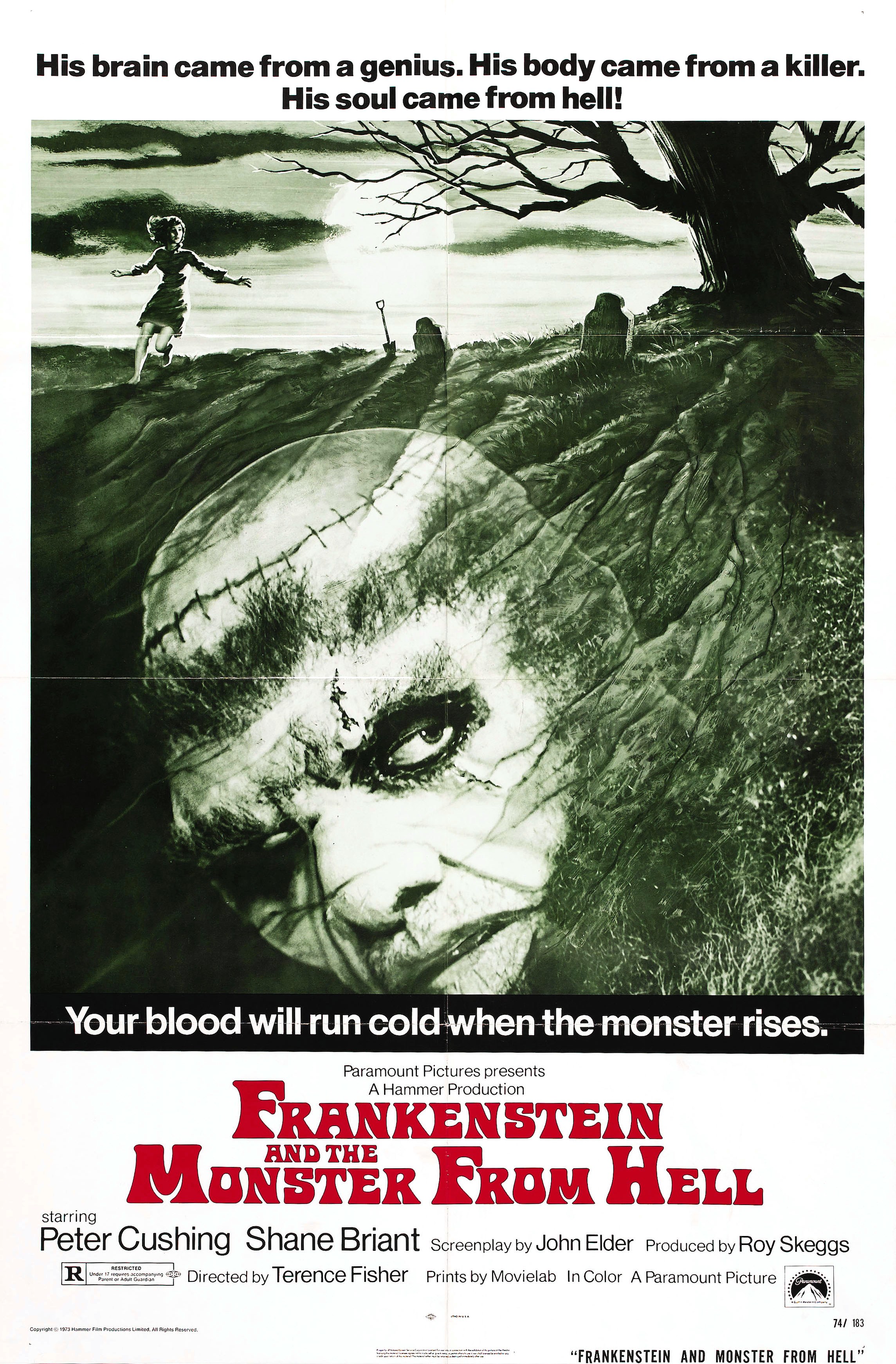

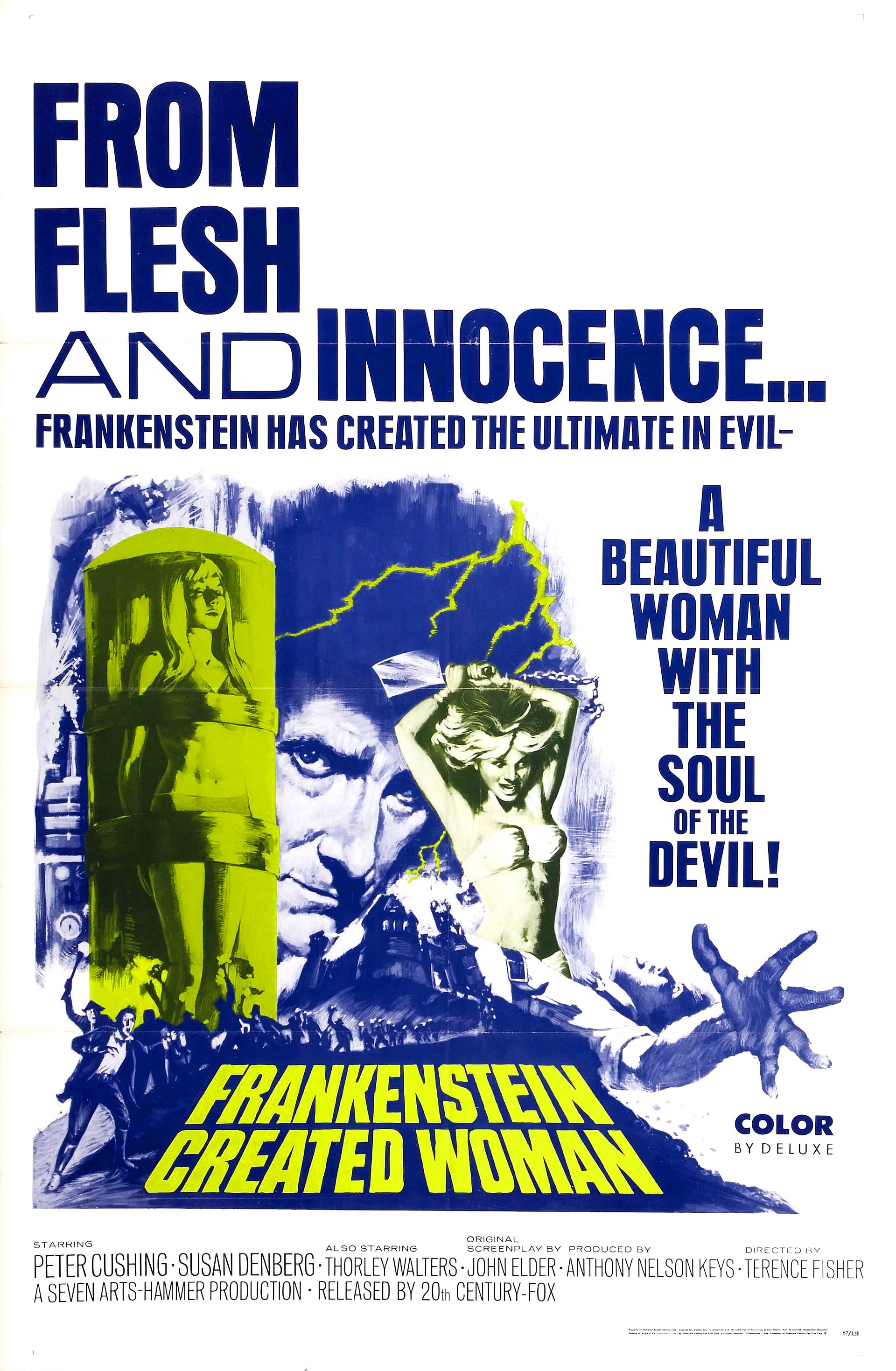

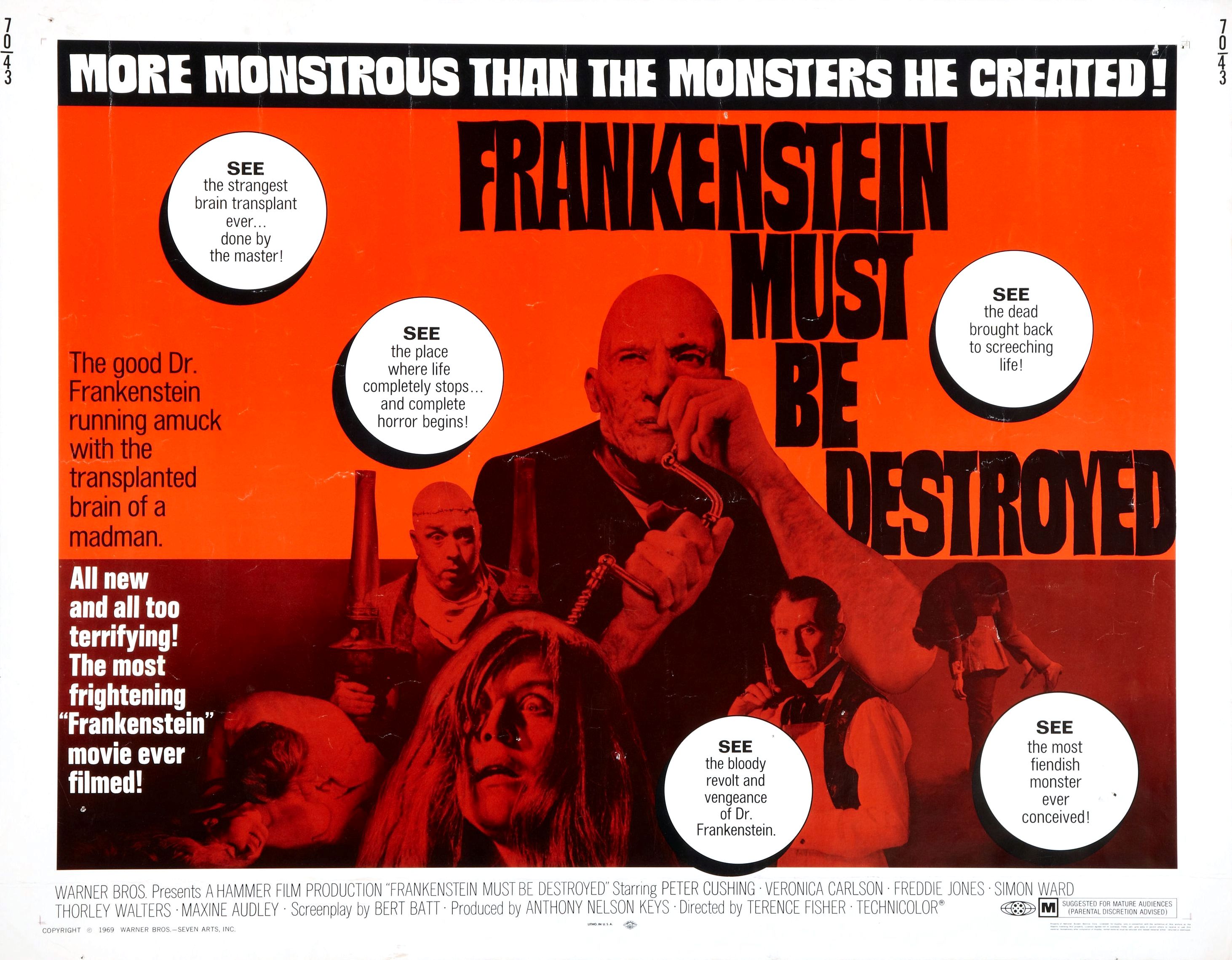

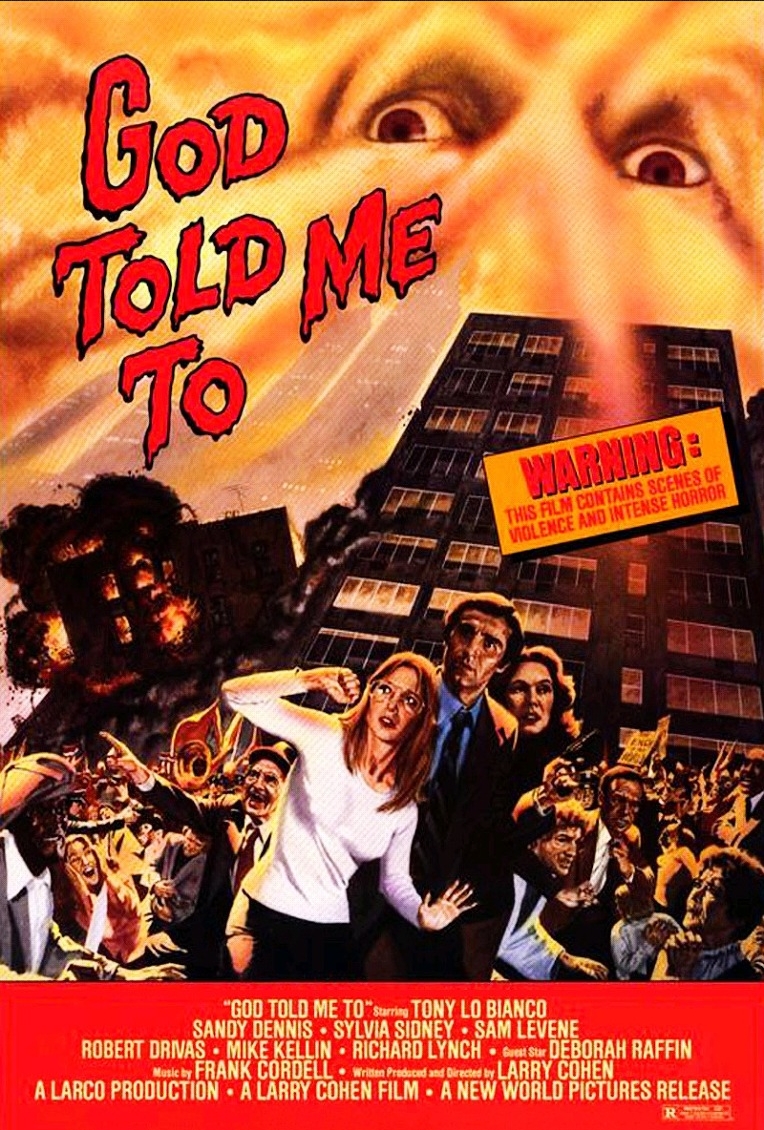

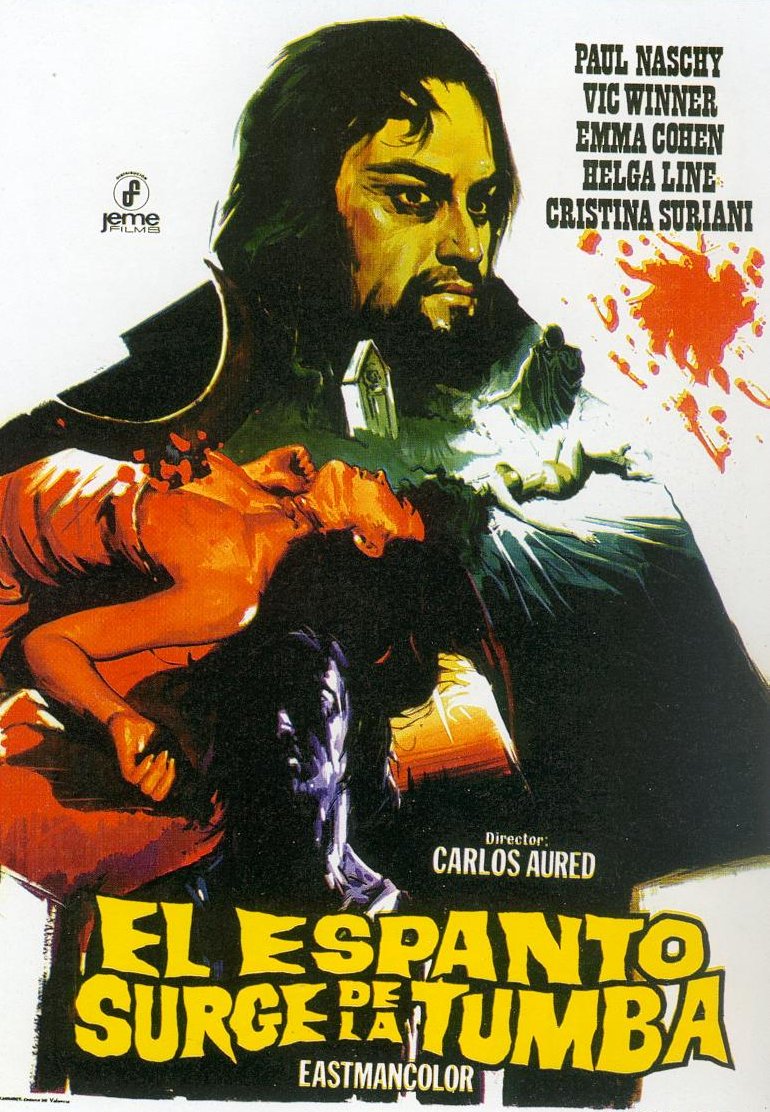

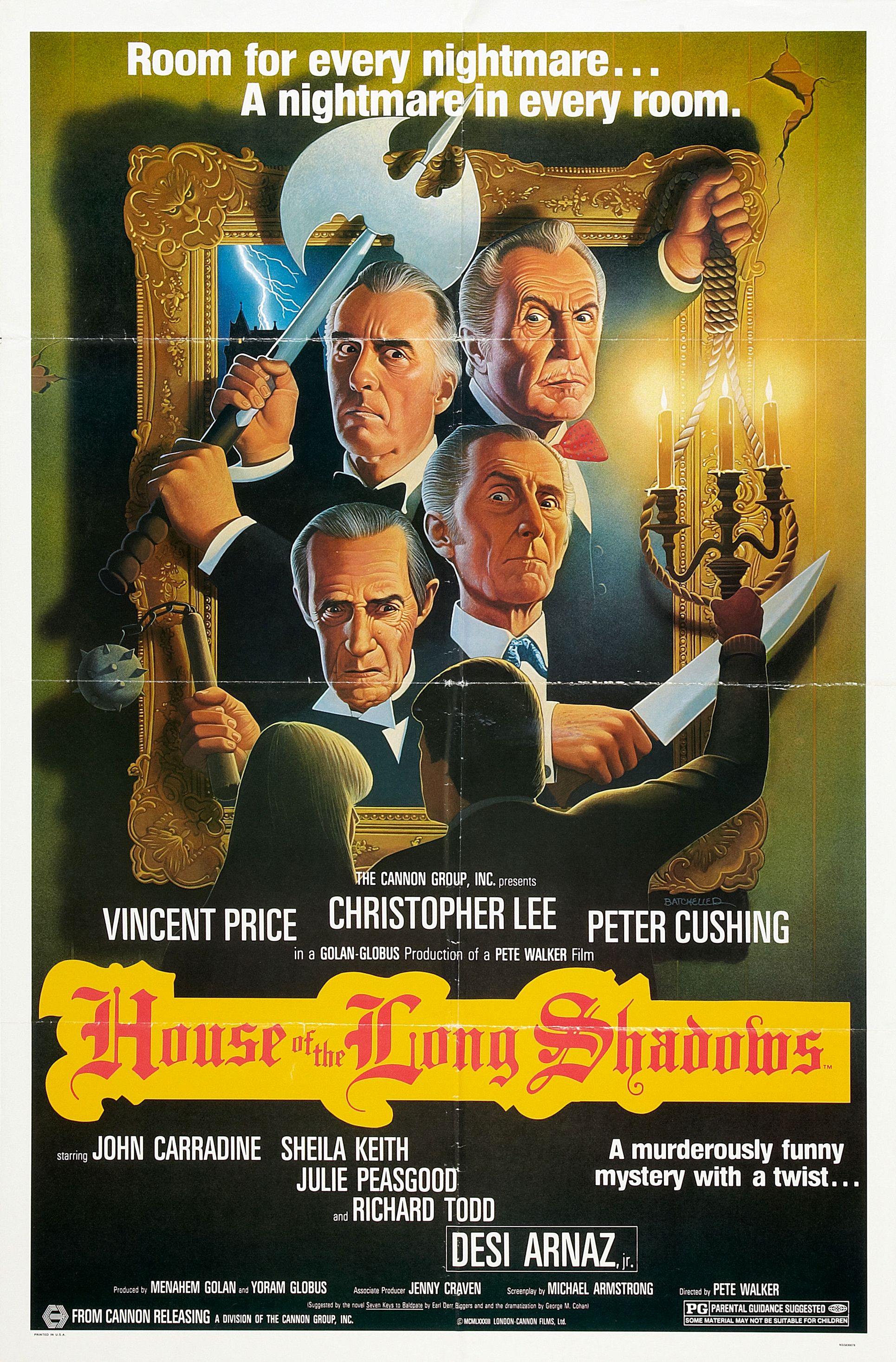

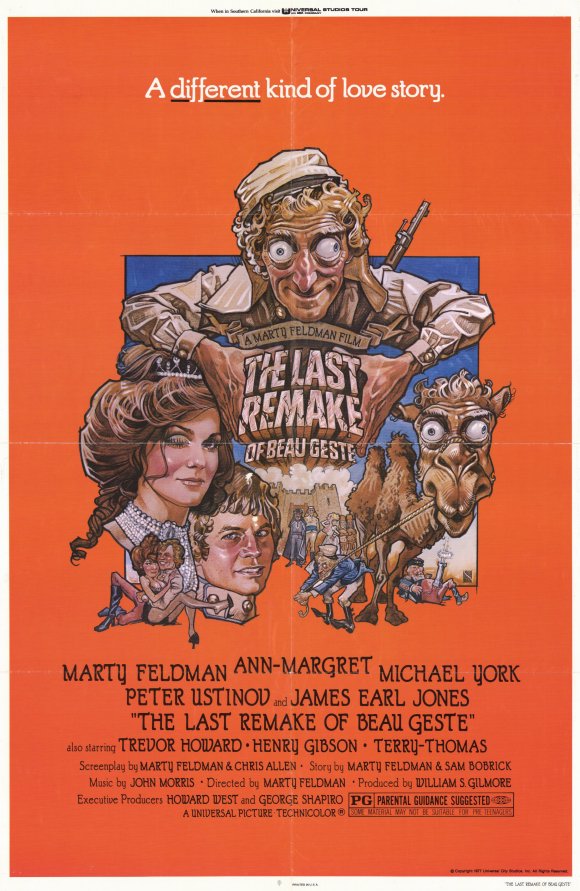

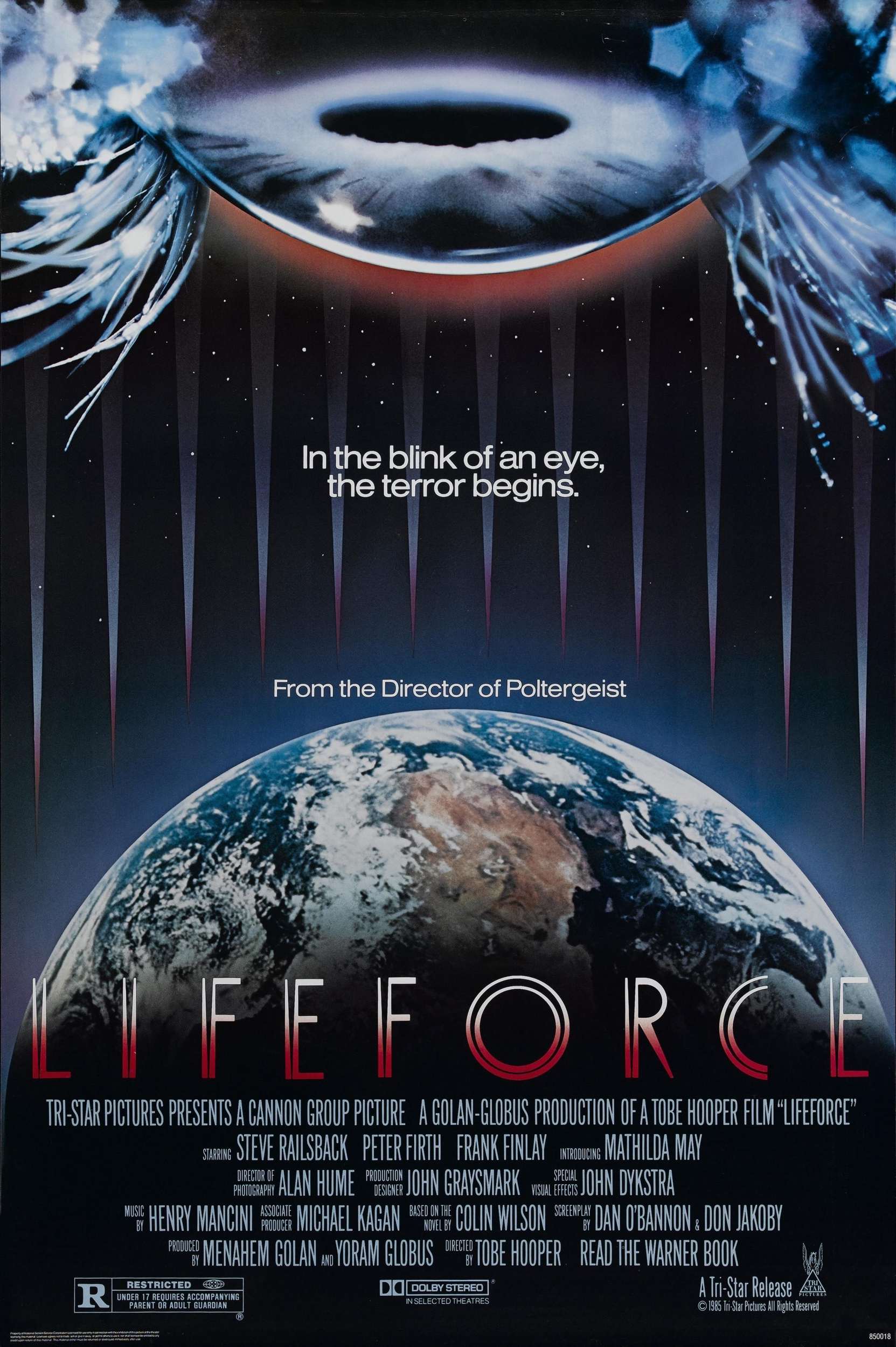

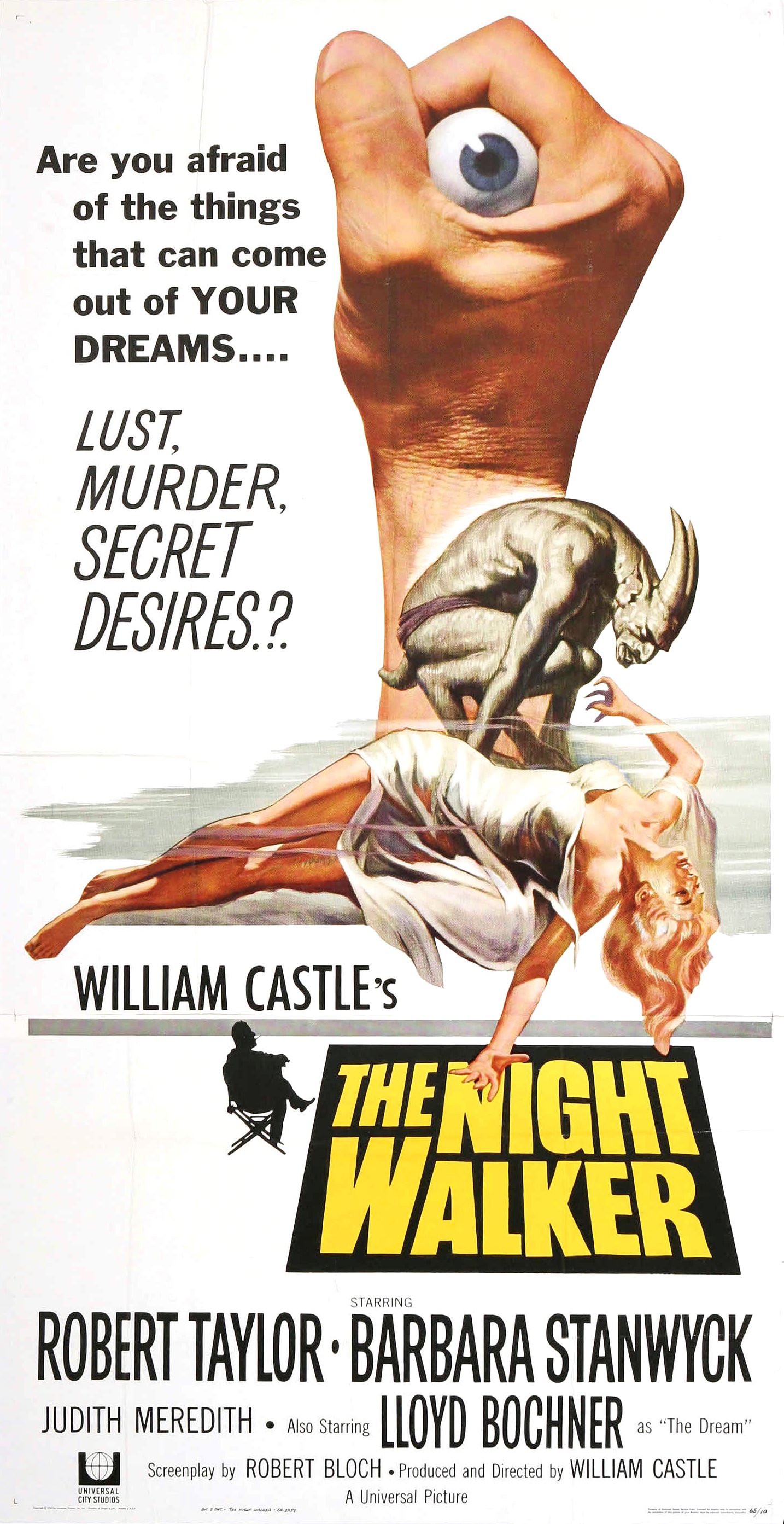

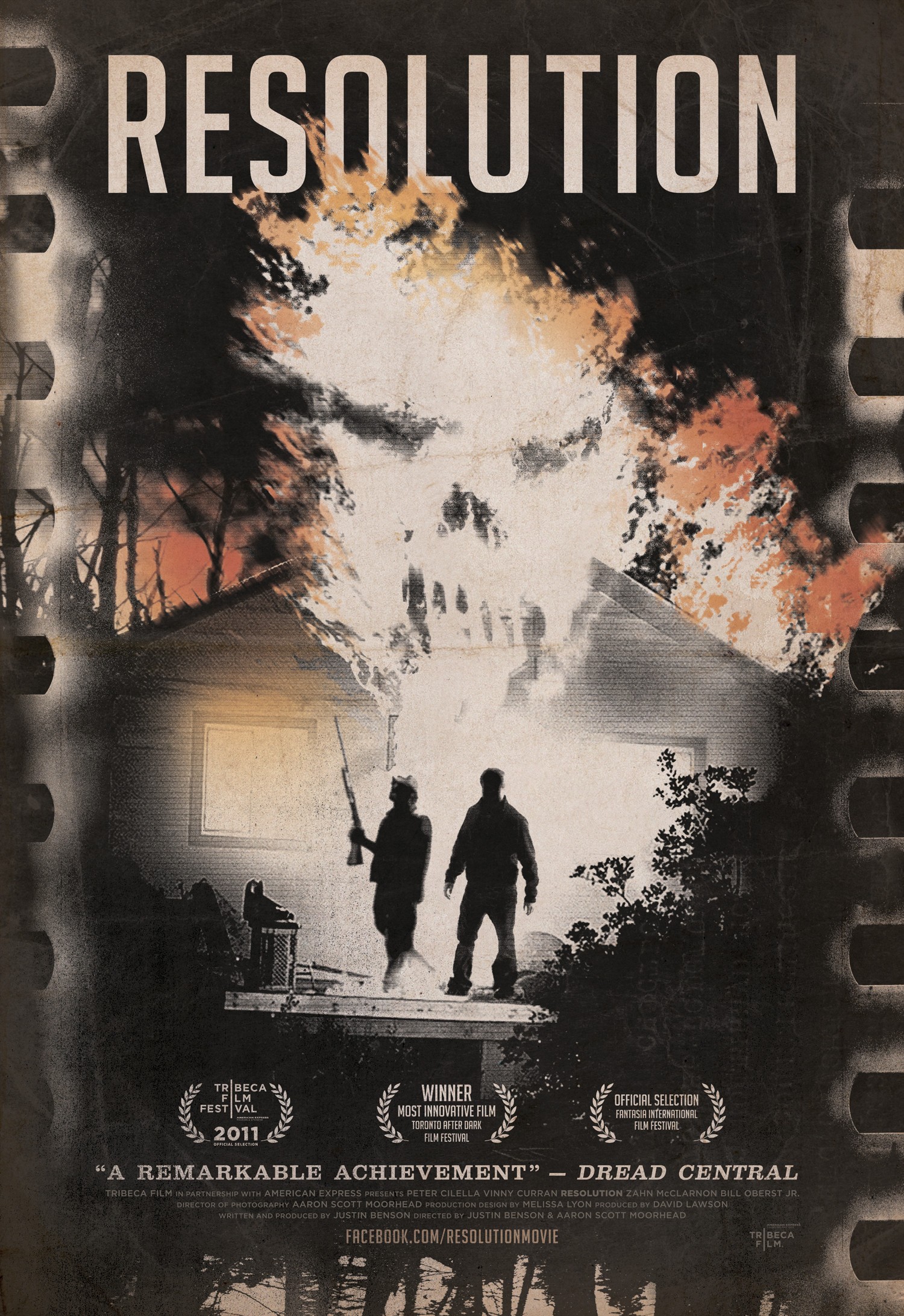

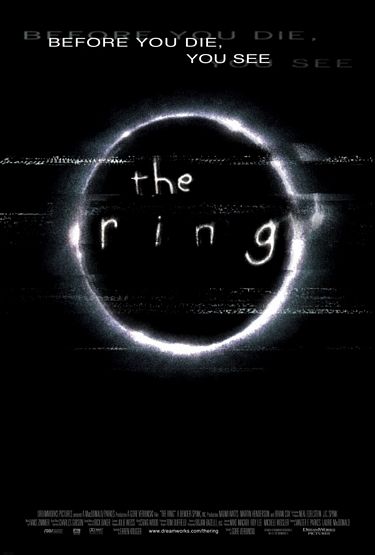

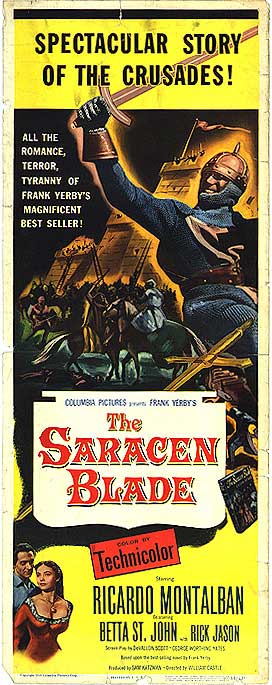

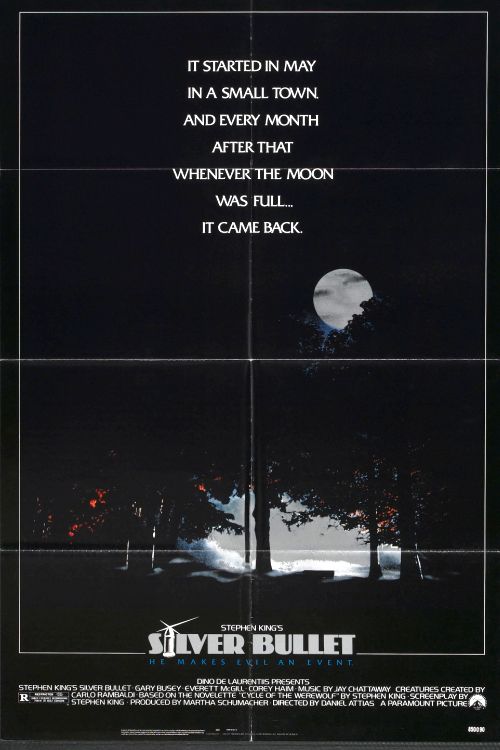

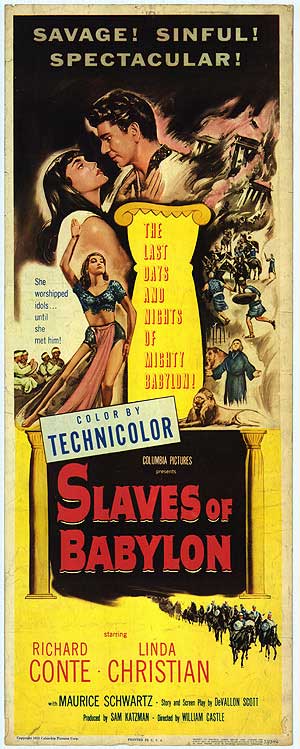

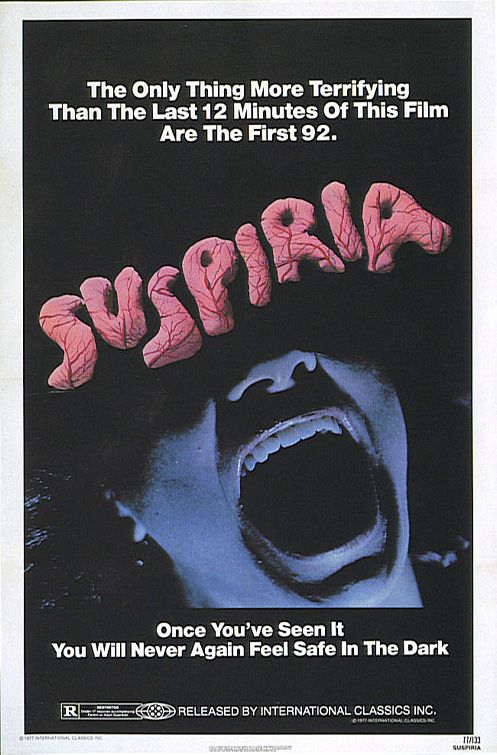

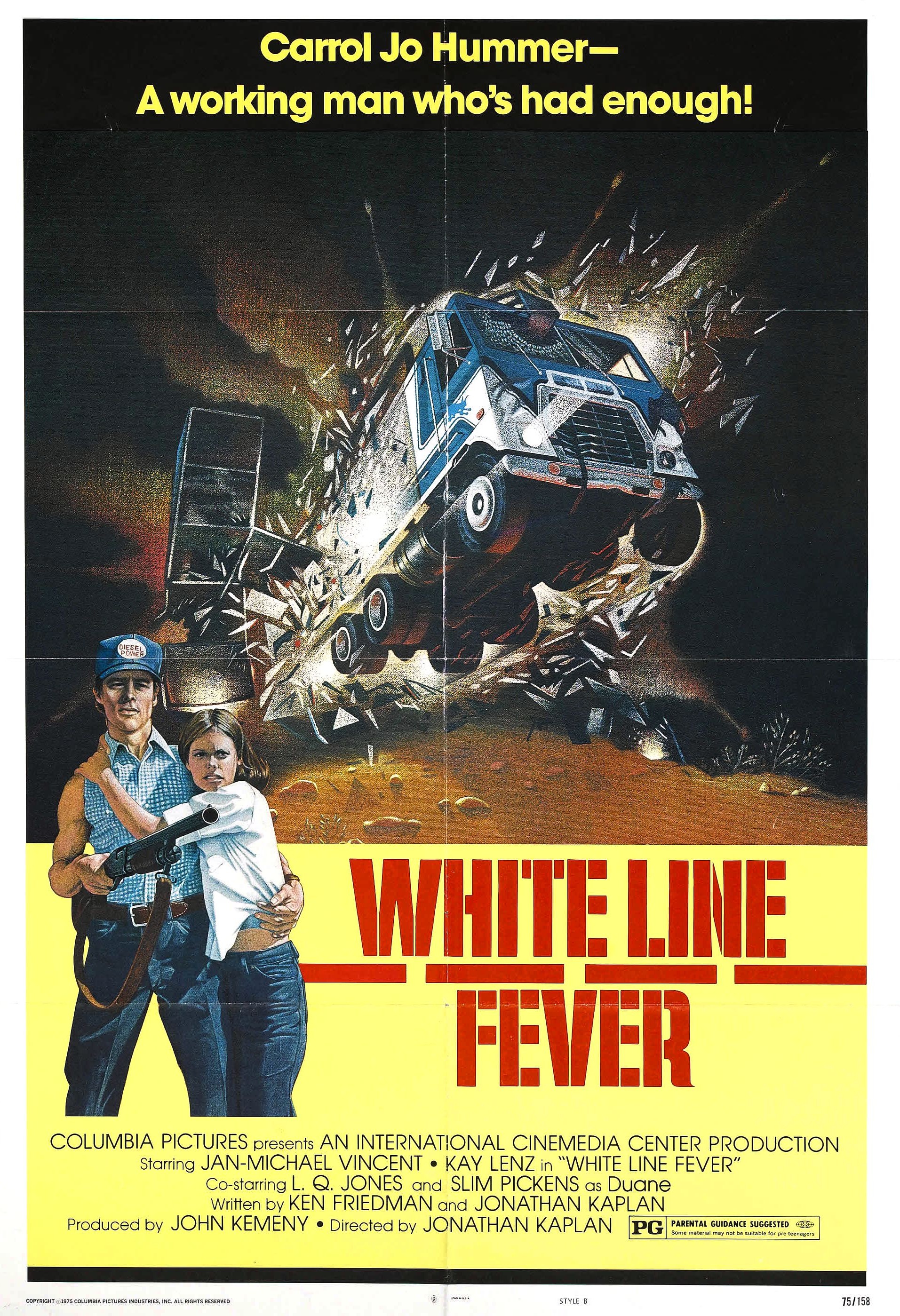

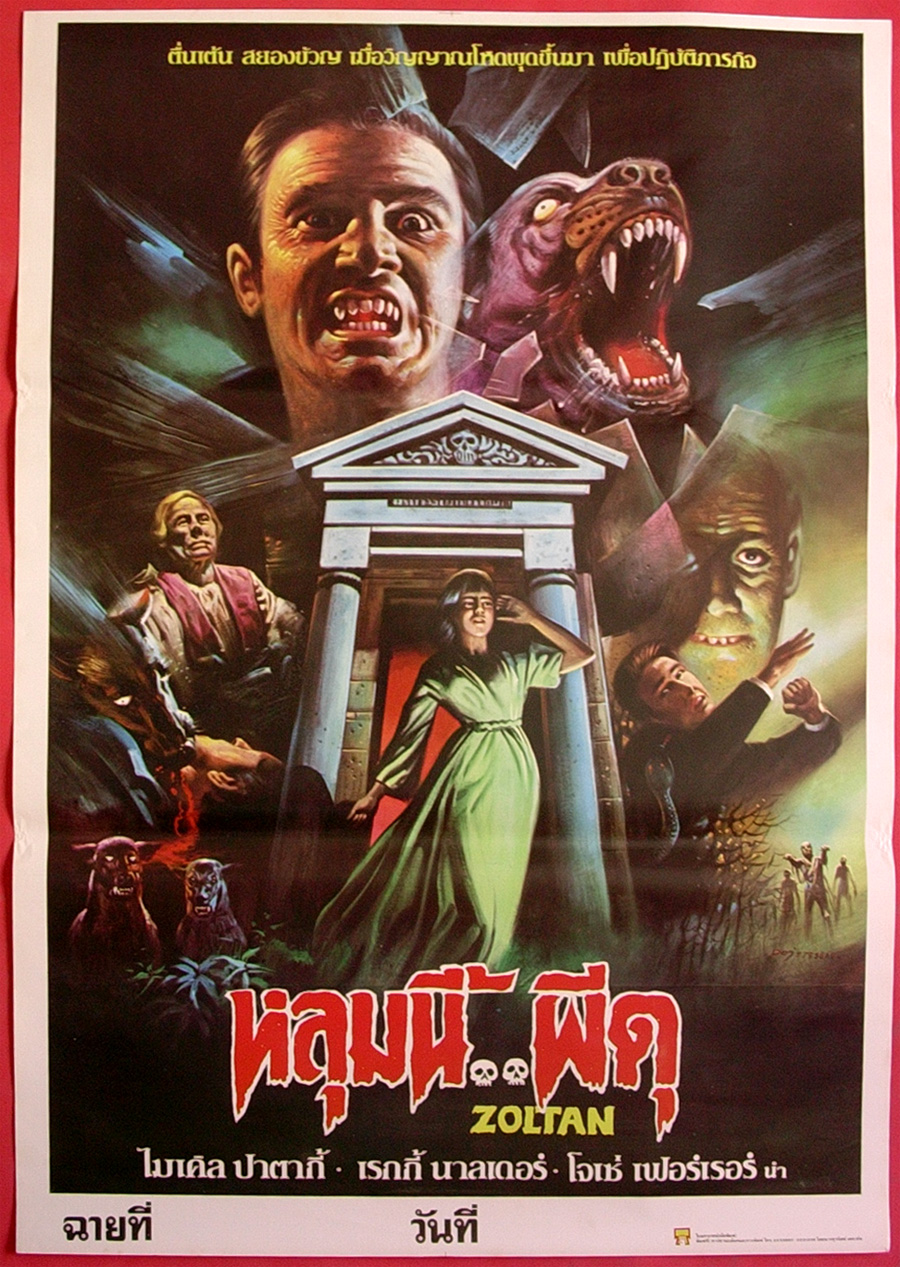

The set of lobby cards and movie poster above also seem designed to keep the antagonist’s identity secret as there isn’t a single solitary image of the title pooch.

The Trenton Family troubles keep mounting as the Sharps Cereal Professor, created by ad-man Vic, is subject to a bit of a scandal. While his slogan is “Nope, nothing wrong here,” there is most certainly something wrong with thousands of people nationwide vomiting potent red cereal dye and fearing internal hemorrhaging. Stephen King does a great job of fitting in the kind of media-fed hysteria that typically ensues after these sorts of scandals, another irrational modern fear. More importantly, plot-wise, it means Vic must leave his family for ten days to deal with this crisis.

Over at the Cambers, an angle grinder does nothing for my own nerves and cuts right through Cujo’s rabies-addled brain. He eventually retreats under the front porch to get away from his noisy family and go gradually crazy in peace and quiet. There are some Camber Family subplots, but they get abbreviated for running time. The short story is that Joe’s wife and son are also conveniently heading out of town.

Despite a few teases, we’re very nearly halfway through the film, and no one has died. Test screenings that got to the car siege quicker reportedly didn’t fare well, however, as audiences just didn’t care about the characters. Admittedly, the slow build proves effective. When Cujo reluctantly retreats through the predawn mist, we know that it is the last time we will see him sane.

The weather posed a particular challenge for Director Lewis Teague. The aforementioned mist had to be manufactured with a naval fogger because the daily gloom took a day off when the scene was scheduled to be shot. The temperature was a greater issue. The car siege is supposed to be held through blistering, dehydrating heat, but, despite references to summer camp and the like, the film was shot during the dead of winter. In a clever bit of movie magic, Jan de Bont held a flame below the camera lens to create the illusion of late summer haze. Glycerine and water created false sweat. And there is, of course, the power of acting.

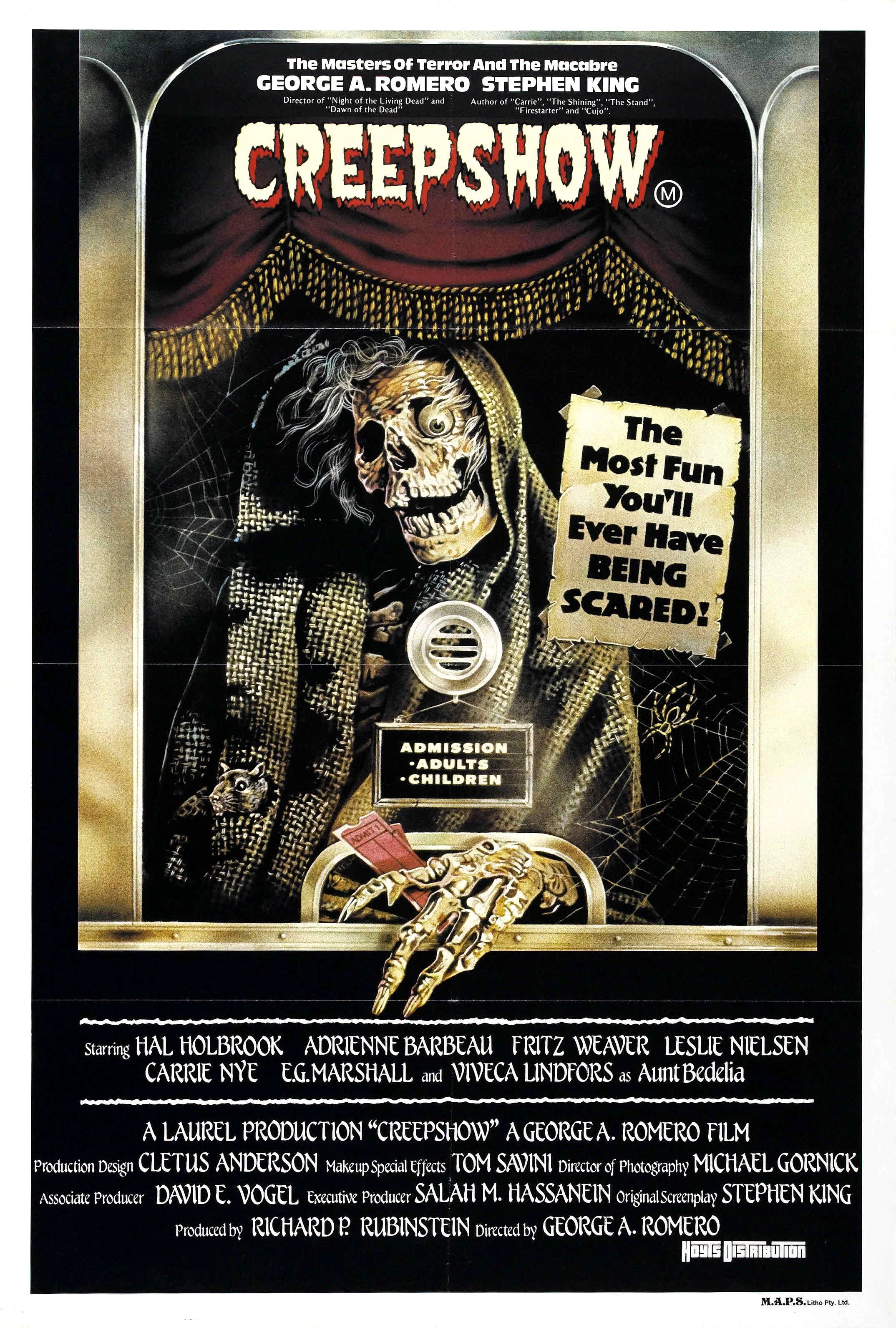

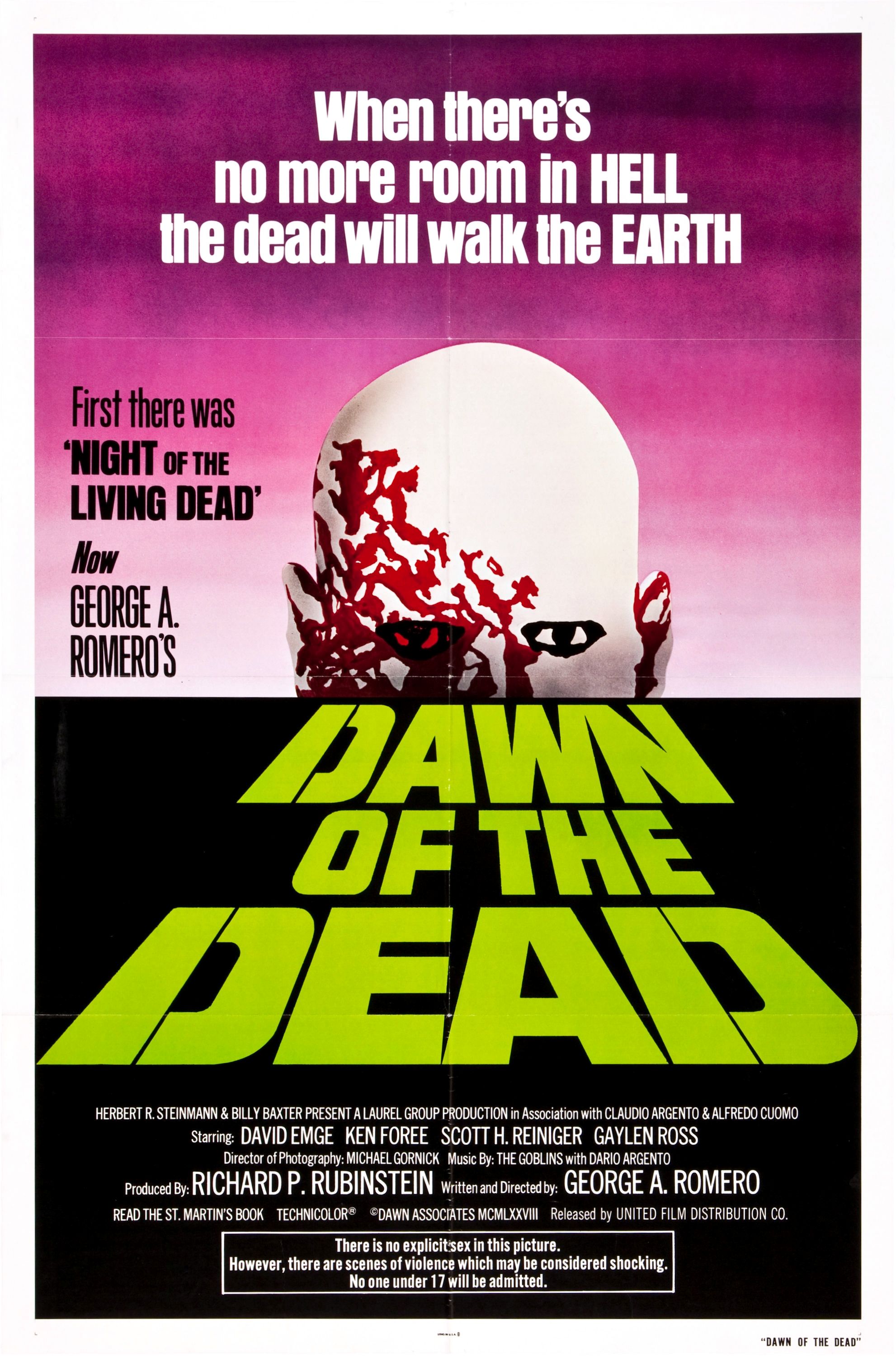

The end result, sadly, is a film I find to be sorely lacking, but noteworthy for a handful of achievements. Call it a near miss. In the wake of Carrie (1976), The Shining (1980), and Creepshow (1982), and with The Dead Zone (1983) and Christine (1983) getting released just months apart later that year, Cujo just doesn’t rate. It is a bit of an unfair comparison, as Lewis Teague just isn’t in the same league as such directing luminaries as Brian De Palma, Stanley Kubrick, George A. Romero, David Cronenberg, and John Carpenter.

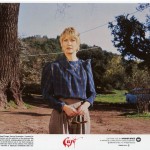

The influence of King’s story and imagery have proven to be far-reaching. The nickname “CuJo” seemed a natural one for celebrated NHL goalie Curtis Joseph, being a portmanteau of his first name and surname. Despite going undrafted, Joseph was a three time NHL All-Star (in 1994 with the St. Louis Blues and in 1999 and 2000 with the Toronto Maple Leafs). In the XIX Olympic Winter Games, he played goalie for gold medal-winning Team Canada, fifty years to the day since their previous gold medal win. While his goalie mask often bore the visage of a snarling dog, a nod to his namesake, Curtis Joseph was recognized for his leadership and philanthropic endeavors by being awarded the King Clancy Memorial Trophy in 2000.

A good dog, indeed.

Unfortunately, the coveted Stanley Cup eluded “CuJo” for the entirety of his career. Amongst goalies who have never played on a Stanley Cup-winning team, he has posted the most career wins to date with 454. After playing for six teams in twenty years, posting 30-plus wins on a record five of them, Curtis Joseph retired in 2010. Despite his statistical achievements, Joseph has yet to be inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame, and, without a Cup or Vezina Trophy and an unfortunate number two spot on the list of most losses by an NHL goalie, there is considerable debate as to whether he ever will.

We hope you enjoyed our little countdown of “A Dozen Diabolical Dogs”. Twelve dogs in thirteen months, but that was hardly my initial intention. It’ll be a while before I have the hubris to tackle another countdown of this scope, methinks. See ya ’round the kennel club!